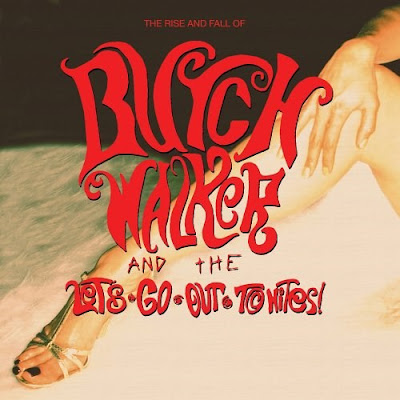

For a long time, I’ve thought that The Rise and Fall of Butch Walker and the Let’s-Go-Out-Tonites! was the most overlooked album in Butch Walker’s discography. Maybe that’s because it was the first Butch album that came out after

I had become a die hard fan, and was, as such, probably the most I’ve

ever anticipated an album. Or because Butch doing glam rock (and making

incredibly obvious David Bowie references) produced the most exciting

live set I think I’ve ever seen him play. Or maybe the underrated feel I

get from this record is the result of the vast majority of these songs

never showing up on “favorite” lists when I chat with other Butch fans.

Whatever the reason, The Rise and Fall doesn’t get a lot of talk,

and it never has. After this record started landing in fan mailboxes in

early July 2006, many of the places that had reviewed Letters favorably

stayed silent; one of my fellow bloggers, a guy who loves Butch every

bit as much as I do, hardly mentioned the album at all until 2009, when

it was one of the records Butch played in full during his winter

“residency” concerts that year; and pretty much every Butch fan I’ve met

on this very site will wax poetic on Letters or Sycamore Meadows, but will seemingly pretend that this album doesn’t exist.

Despite all of this, I absolutely adore The Rise and Fall, and

have, at certain times, considered it as Walker’s second greatest album.

I love serious, emotive Butch as much as the next fan—and we get a

certain amount of that here: see the gorgeously elegiac piano ballad

that is “Dominoes”—but you can’t fault a man for being happy, and the

Butch Walker on The Rise and Fall sounds like a guy who is ready

to throw the biggest, loudest, rowdiest, and glammiest summer rock party

of all time. Dropping in the middle of a summer that I still hold among

my most memorable—that was the first year I saw Butch live, after all—The Rise and Fall has

struck me ever since as the perfect summer party record. The

short-lived backing band that was the Lets-Go-Out-Tonites had a lot to

do with that, contributing mountainous back-up vocals (the operatic

“Oooh...Aaah...” intro track, which hypnotically weaves itself in and

out of infectious opener, “Hot Girls in Good Moods”), baroque pop

arrangements (“Ladies and Gentlemen,” which features vintage piano,

guitar, and bass sounds that could have been on a Beatles record), and

plenty of hand claps to go around (the especially glammy lead-off

single, “Bethamphetamine”). The band brings a lot to these songs, making

them sound explosive and out-of-control in the best way possible. Next

to the perfect arrangements and studio sheen of Letters, The Rise and Fall legitimately

sounds like it could have been made by a different artist in a

different decade. It was the beginning of a streak of records where

Butch would remake himself every time he entered the studio.

The album doesn’t get any more conventional as it crashes headlong

into its second act, either. Abbey Road strings drench “We’re All Going

Down” and “Dominoes,” to the point where they both sound like they could

have been extricated right from the center of a classic Broadway

musical (especially the latter). “Paid to Get Excited” is an

anti-conformist, anti-religion, anti-government tirade, and the loudest,

angriest, and most political song Butch has ever written. He hates and

regrets the song now, but what would a spontaneous knee-jerk album like

this one be without a blazingly misguided moment of indulgence? Speaking

of indulgence, is that a backwoods alt-country hymn on “Rich People Die

Unhappy”? And is Butch seriously duetting with a major label pop star

(Pink) on “Song Without a Chorus,” an anthem about the inequities of pop

music and mainstream radio? Yep, Butch pretty much did whatever the

hell he wanted on this album, and while the results aren’t half as

cohesive as Letters or Sycamore Meadows, there’s an

undeniable charm to hearing him hit half a dozen genres in under 45

minutes. The fact that he knocks the ball out of the park most of the

time anyway only makes The Rise and Fall’s bizarre mission

statement that much more lovable. As Butch sings on one of this album’s

songs, “we’re hotter when we don’t give a damn.”

All that said, The Rise and Fall is far from a “fucking around”

kind of record. Some of the styles Butch tried here would turn into

entire career directions on future albums. “Rich People Die Unhappy” and

the anthemic, California-folk finale, “When the Canyons Ruled the

City,” unveiled a passion for throwback roots and country music that

Butch would explore heavily on Sycamore Meadows (and at least

passingly on every other record he’s made since), while it isn’t

difficult to hear a “la-la-la” kick-box rocker like “Too Famous to Get

Fully Dressed” as the genesis stone that inspired 2011’s The Spade.

And if the agile string arrangements and sunny guitar solos of “The

Taste of Red”—which boasts the record’s most blissful hook—didn’t lead

to the Beatles pop pomp of 2010’s I Liked It Better When You Had No Heart, then the resemblance was certainly still obvious enough for Butch to make it a live show staple during that era.

Of all the Butch Walker albums, The Rise and Fall is the most

dynamic, if only because it concludes in a completely different place

than where it starts. Storming out of the gate with loud, early-1970s

flamboyance, this record somehow finds its way from the decadent party

scene of Los Angeles to the sun-soaked valleys and arches of Laurel

Canyon. The conclusion of the trip is hinted at in the balladic

penultimate track, “This is the Sweetest Little Song,” a delicate

lullaby awash in falsetto vocals, relaxed acoustic chords, and yet

another string arrangement. But instead of ending the record on a gentle

note, Walker saves the best and most ambitious song for last. “When the

Canyons Ruled the City” is a ringing 1970s singer/songwriter anthem,

complete with a rafter-raising sing-along refrain and verses that

personify the canyons of Hollywood Hills. It’s not an idea that sounds

strong on paper, and in lesser hands—or in pretty much any other hands this

side of Laurel Canyon natives like Dawes—the song wouldn’t work at all.

But thanks to Butch’s oft-present hint of sarcasm and a dramatic,

larger-than-life vocal delivery, we can buy into a tale of Laurel as a

girl who was “pretty hip in younger years,” or Beachwood as a “boheme

from the sexy ‘60s scene,” and the arguments the two often have “on the

terms of selling out.” It’s a patent ‘70s stoner anthem, transplanted to

an album that came out in 2006, written and sung by a guy who was born

at the tail end of the ‘60s and grew up enthralled with ‘80s hair metal.

In short, it’s a song full of contradictions, but by the time it

reaches its triumphant, Queen-sized climax, it’s hard to imagine

anything sounding more authentic. It’s no surprise fans still yell for

“Canyons” at the end of every Butch Walker encore.

I remember the day this record arrived in my mailbox, the first album I

had ever gotten my hands on prior to the release date. I remember

blasting these songs on repeat—in sequence, on shuffle, whatever—for

days and weeks straight. I remember the night of August 1st that year,

the night Butch came to Detroit on a 110-degree day and stormed onstage

to the opening riff of “Hot Girls in Good Moods.” To say this album

means a lot to me is an understatement. It captures that summer—a

snapshot of my youth, a parade of long, hot days, filled with promise

and the best soundtrack imaginable—and refuses to let it go, even seven

years on. I think that’s why The Rise and Fall of Butch Walker and the Lets-Go-Out-Tonites! is

still my brother’s favorite Butch Walker album. We built memories

around this record, around playing it religiously and around seeing

Butch live for the first time, that we’ve been trying to duplicate ever

since, with every record we share and every live show we take in

together. When I hear these songs, they remind me of him and how, as

brothers five and a half years apart in age, we found connection and

shared some of the happiest moments of our lives through music. And I

know that sounds cheesy and overly sentimental, but that’s what music

can do: it can give us the best of ourselves when we’re alone and broken

and the best of the people around us when we’re sharing a triumphant

moment with others. At different times, Butch’s music has consoled me in

solitude and soundtracked communal euphoria, and The Rise and Fall is absolutely his most communal record to date. If you’ve overlooked this one in the past, listen again.

No comments:

Post a Comment